Remembering the Cholera Epidemic of 1832

- Details

- Hits: 22712

The lifeline of a living Congregation parallels the life of the Church. Founders and Foundresses are often influenced by movements and trends in the history of the Church. Where people suffer the Church usually responds. Certainly this was true of Edmund Rice. He always read and met “the signs of the times.” In the early years of the Congregation, there were times when the schools were closed and handed over to the civic authorities because of the dreaded Typhoid fever or Cholera epidemics which periodically swept through Ireland.

In 1816 the Brothers were just completing the building of the famous North Monastery in Cork when they were asked to allow the building to be used for those dying of Typhoid fever. A Catholic doctor donated beds and installed windows throughout the building and for the next year their new school became a temporary hospital. It was 1818 before the school was again open to the admission of boys.

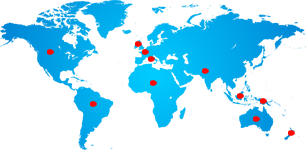

The early spring of 1832 was unusually fine in Ireland. But the people were worried. They had heard that a vigorous form of Asiatic or Blue Cholera had run through Asia and was on its way across Europe. Many hoped that Ireland's situation as an island on the western edge of Europe would save it. But when the cholera reached Paris and London, moving westward, prayers were offered that the dreaded scourge would not reach that far.

In March of that year cases were reported in Dublin and Belfast. The Cholera had arrived.

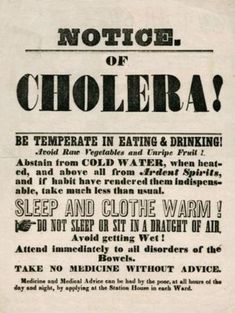

Dublin was an old city and since the Act of Union of 1800 it was a very poor city. The sanitary condition of the city had not been attended to for a long time. With poor living conditions and unsanitory water supplies, the disease raged through the poorer parts of the city which were crowded with a population sunk in indescribable misery. Every morning a fresh list of the dead was posted on the doors of the churches. Quarantine was encouraged to slow the rapid spread of the disease and to quell public hysteria. There was fear and depression all over the country. Between fifty and sixty people died each day in Dublin. The Archbishop of Dublin, the clergy and the religious of the city helped in nursing and comforting the victims.

Soon, however, the cholera spread outside the city. Public authorities everywhere took measures to meet this dreadful scourge. Temporary hospitals were set up in addition to those already existing. Belfast, Cork, Drogheda, Thurles, Galway, Dungarvan became in quick succession scenes of awful suffering.

Edmund Rice directed that his Brothers should help wherever they could. In Thurles the Brothers gave up their monastery and schools to the Board of Health to be used as hospitals and they looked for lodgings for themselves. In Dungarvan the Brothers likewise surrendered their house and schools and went to live in the empty house of a lady who had fled the country.

The cholera came to Cork a month later than Dublin. There was panic in the city. The number of deaths in Cork was so great that some people lost all hope and refused to go to the hospital. In Cork also, the Brothers helped. The Sisters of Charity, then only five years established in Cork, did heroic work, as did Archdeacon O'Keefe and the famous Fr. Francis O’Mahony.

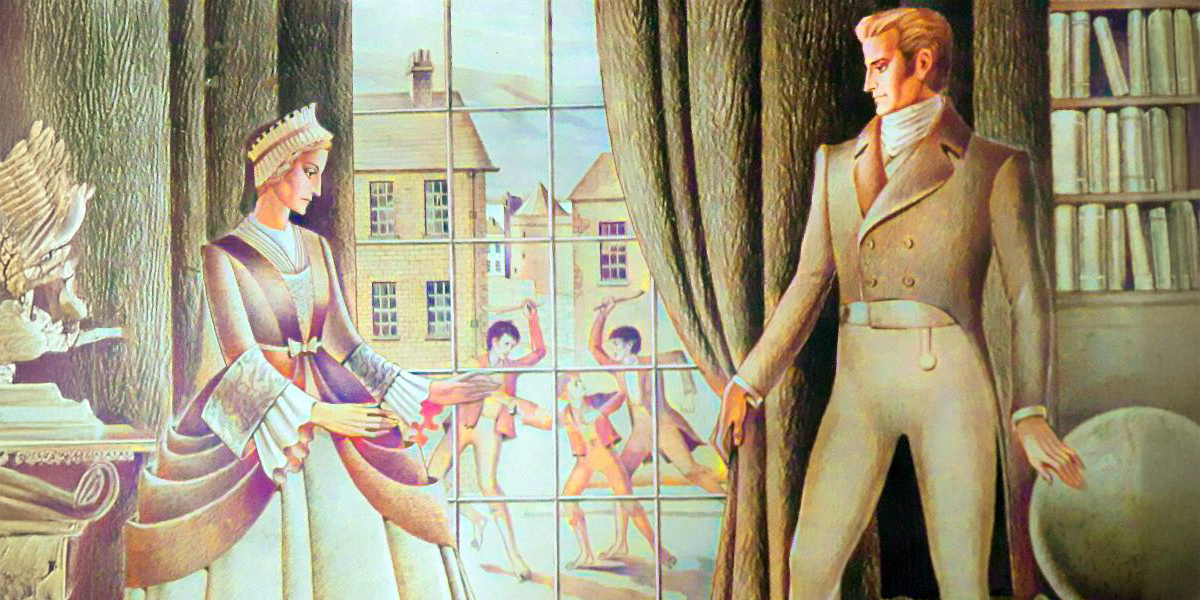

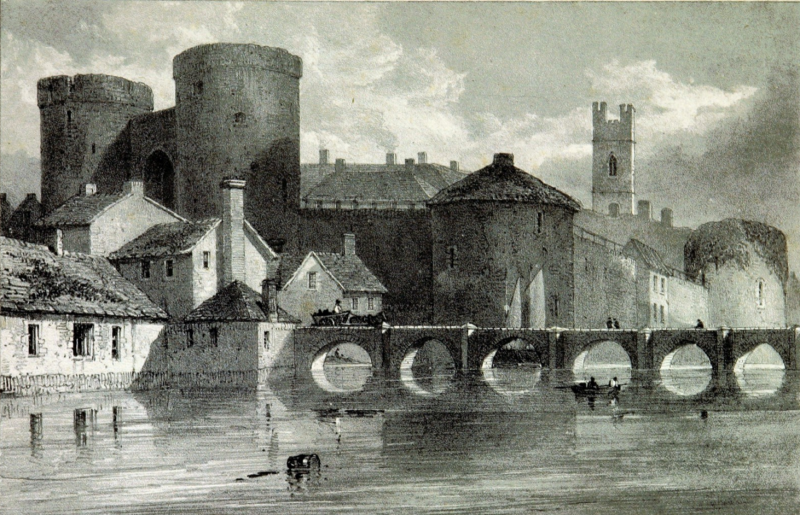

There was a shortage of hospital accommodation in Limerick. A Board of Health was established. Barrington’s, the principal hospital in the city, could not cope. Edmund Rice advised his Brothers to help all they could. They placed their house, their new school (just built) and themselves at the service of the Board. The schools were closed until further notice. Sexton Street schools were fitted up as a hospital. The upper and lower rooms, each 64 feet long, were supplied with beds, the women upstairs and the men downstairs.

On May 26th the Cholera set in with great malignity. On the night before, the city had been covered with a deep and damp fog that almost suffocated the people. The first Cholera patients were brought to St. Michael’s Hospital (Sexton Street Schools). Limerick had no nuns at the time. The Presentation Sisters did not come to Limerick until 1837 and the Sisters of Mercy in 1848. Two brave Clare ladies, Miss Reddin and her niece, Miss Bridgeman (aged 19 years) took up residence in the parlour of the monastery and superintended the school hospital, day and night. These two great ladies had charge of a hostel for street girls. These girls worked side by side with them as nurses in the hospital. Some years later, Miss Bridgeman entered the Sisters of Mercy and became famous for her heroic work for the soldiers in the Crimean War, 1854.

Barrington’s and St Michael’s hospitals both filled rapidly. The cries of the people were heard daily in various parts of the “English” and “Irish” town. The appearance of the hospital carts in the streets spread the wildest confusion. Labourers with carts collected manure from the lanes and spread slack lime on the footpaths and the channel ways to try to counter the spread of the disease. Houses were whitewashed, sentries were placed at the entrances to towns. Bedding and blankets were distributed to the poor. Wealthy families went to the seaside or to friends in the country. No mail coaches ran either into or out of the city. There were hearses on the streets every hour of the day. Many poor people died on their way to hospital.

The Brothers of Sexton Street went at all hours among the male patients in Barrington’s and St Michael’s. They sat by their bedsides, rubbed down aching limbs and prepared them for the Last Sacraments. There were ten to fifteen deaths each night. The cholera lasted six weeks in Limerick.

Brother Virgilius Jones who had lived with some of the Limerick Brothers recorded the following: “From the details which have come down to us of the labours of the Brothers during the epidemic in Limerick, it is clear that no pen could do justice to their charity and patient endurance, in all their ministrations. All day long they were to be seen at the bedside of the sufferers attending to every call, to soothe every pang, using every appliance possible to keep down the burning fever or to ease their tortured limbs. The night also found the Brothers at their post, the silence of which was only broken by the heart-rending cries of the sufferers, calling aloud for the Brothers by their names, and whose very presence at the bed-side seemed to have a soothing effect." He goes on to describe the conditions of the locations, the entrance crowded with coffins awaiting burial and with coffins waiting for corpses, the Brothers stepping over 10 or 15 bodies each morning.

Brother Virgilius Jones who had lived with some of the Limerick Brothers recorded the following: “From the details which have come down to us of the labours of the Brothers during the epidemic in Limerick, it is clear that no pen could do justice to their charity and patient endurance, in all their ministrations. All day long they were to be seen at the bedside of the sufferers attending to every call, to soothe every pang, using every appliance possible to keep down the burning fever or to ease their tortured limbs. The night also found the Brothers at their post, the silence of which was only broken by the heart-rending cries of the sufferers, calling aloud for the Brothers by their names, and whose very presence at the bed-side seemed to have a soothing effect." He goes on to describe the conditions of the locations, the entrance crowded with coffins awaiting burial and with coffins waiting for corpses, the Brothers stepping over 10 or 15 bodies each morning.

The six-month siege of cholera in Limerick found 525 patients being cared for, and out this number there were 225 deaths. A later Superior General, Brother Louis Hoare, was seen carrying out corpses on his back.

Towards the end of the outbreak the Board of Health saw the necessity for a convalescent home for patients recovering from cholera. The Brothers gave over their other schools in Clare Street. It was a big building and had housed 300 pupils.

Edmund proudly praised the work of the Brothers in a letter he wrote to Mother Austin McGrath in Dungarvan on June 12th, 1832: "Our Limerick Brothers are attending the poor cholera patients in the Hospitals. They give a frightful account of the ravages it is making there... Sixteen sent dead out of the school - which has been turned into a hospital - one morning. I am not one bit in dread that a Priest, Nun or Monk will sink under its direful hand." While his trust in Providence was not realised as regards the priests – two died, one in May and the other in November - no Brother or nurse in St Michael’s Hospital caught the disease.

(Acknowledgement of the sources: John E. Carroll, Barney Garvan, Columba Normoyle, Al Houlihan)